A Journey

Of Distinction

To Indochina

A Journey Of

Distinction To Indochina

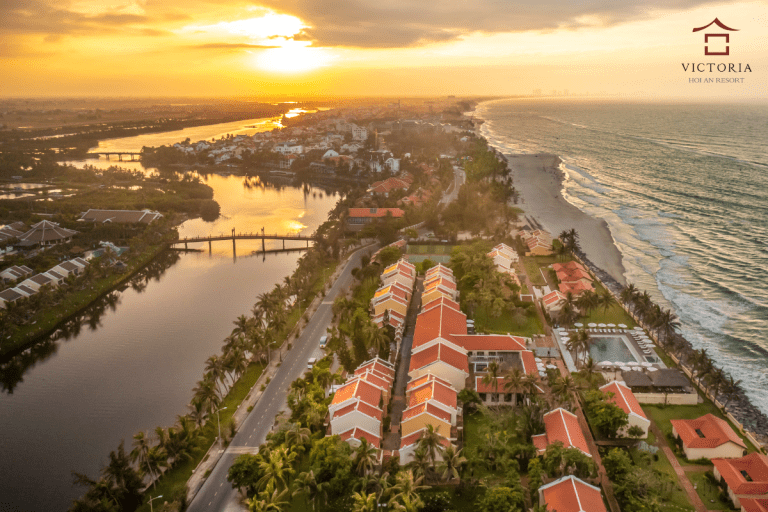

Destination

Victoria Hotels & Resorts are blessed to be located in some of Southeast Asia’s most iconic destinations. Our properties are as distinct as their surroundings, each a unique blend of cultural influences both past and present.

Special Offers

Experience

Victoria Cruises

Life in the Mekong Delta is inextricably linked to its many waterways. Experience the lush Vietnamese countryside in comfort and style on day and overnight journeys with Victoria Cruises.

Victoria Sidecar

Leave the driving to us while soaking in the sights from the unique perspective of a vintage sidecar with both hands free to document your epic adventure.

Victoria Speedboat

Take the comfortable Victoria Speedboat - the best way to travel between Chau Doc, Vietnam and Phnom Penh, Cambodia with bonus views of the beautiful Mekong Delta.

Victoria Sailing

Join us to create unforgettable memories at the beautiful Cua Dai beach with Victoria Sailing. Be on top of the world when experiencing our unique and exciting water sports.

Victoria Cruises

Life in the Mekong Delta is inextricably linked to its many waterways. Experience the lush Vietnamese countryside in comfort and style on day and overnight journeys with Victoria Cruises.

Victoria Sidecar

Leave the driving to us while soaking in the sights from the unique perspective of a vintage sidecar with both hands free to document your epic adventure.

Victoria Speedboat

Take the comfortable Victoria Speedboat - the best way to travel between Chau Doc, Vietnam and Phnom Penh, Cambodia with bonus views of the beautiful Mekong Delta.

Victoria Sailing

Join us to create unforgettable memories at the beautiful Cua Dai beach with Victoria Sailing. Be on top of the world when experiencing our unique and exciting water sports.

News

Embark on a journey filled with captivating experiences, explore diverse destinations, savor regional delicacies, and immerse yourself in rich cultural traditions, and stay abreast of the latest news from Victoria Hotels.

These are the things you can’t miss about Pimai Lao Festival, the traditional New Year of Laos

Immerse yourself in the vibrant sounds of music and laughter as you celebrate Pimai Lao, the traditional Lao New Year, at Victoria Xiengthong Palace in Luang Prabang this April! Victoria Xiengthong Palace is the perfect place…

Victoria Hotels & Resorts

Explore Southeast Asia’s Elegance with Victoria Hotels & Resorts

Dive into the heart of Southeast Asia’s beauty with Victoria Hotels & Resorts. Our unique collection spans iconic destinations, offering a perfect blend of cultural heritage and modern luxury.

From the ancient streets of Luang Prabang to the serene waters of the Mekong Delta, each property provides a gateway to explore, relax, and experience the unparalleled charm of Indochina.

Discover our curated experiences, from river cruises to cultural immersions, ensuring your journey is nothing short of extraordinary.

Visit us to start your unforgettable adventure.

Discover Unmatched Elegance & Adventure with Victoria Hotels & Resorts

Embark on an unforgettable journey through Southeast Asia with Victoria Hotels & Resorts, where luxury meets tradition.

Experience the region’s captivating beauty, from tranquil rivers and lush landscapes to historic cities, through our curated collection of properties.

Each resort and hotel invites you to immerse in local culture, indulge in exquisite comfort, and explore breathtaking destinations. Start your adventure here.

Victoria Hotels & Resorts We are member of TMG